The death

of Venus

by

Dimitrios Otis, contributing writer ,Vancouver Courier. 03/07/2007

Photo of Michael Turner by Dan Toulgoet

Gazing

around the dim interior of the Venus Theatre, Michael Turner

is sad. The Vancouver author has been told the longtime porn

palace in the Downtown Eastside will soon be demolished.

A

shabby curtain partially obscures a few men sitting on metal

chairs on the flat main floor of the cavernous auditorium. On

the big screen is a fuzzy video image of bluish skin, beaming

out from a large, antiquated floor projector. Turner has returned

for a last look. He first came here in 1978. He was underage

and the experience made such an impression on him that he used

it as the opening to his novel The Pornographer's Poem, which

won a B.C. Book Prize in 2000.

"I

was in Grade 10 when I first went to the Venus Theatre," Turner

tells me. "It was a wet November night and I was with one of

my best friends. We had a desire to see what lay behind those

tiny adult film ads in the Province newspaper's sports section."

What

lay behind those tiny ads were giant celluloid bodies writhing

in lurid colour, and there have been a lot of them since the

Venus Theatre started showing sex movies in 1970. But the building

and much of the block will soon be yet another condominium development.

Most

of us have passed by the grimy washed-out pink stucco structure

at 720 Main St. Far fewer have dared enter, especially since

tales of drug use, low-track prostitution and public sex inside

the theatre have surfaced, including an award-winning expose

in this paper in 2004.

So

as word got out in the fall of 2006 that Vancouver-based Porte

Realty had bought the property, along with most of that entire

block, there was little lament. Porte plans to restore three

buildings at the corner of Main and Georgia streets that comprise

the Hotel Pacific. They will become non-market housing, and

the Imperial will make way for nine floors of market condos

with a standard main level of retail. People may gripe about

yet more condos going up in the Downtown Eastside but there

will surely be line-ups to buy in. Throughout its long history,

there was rarely a line-up at the Venus.

News

of the redevelopment was noticed by heritage researchers, who

belatedly noted that the building the

Venus occupies is actually an original vaudeville theatre, called

the Imperial, which opened in 1912. At a meeting of the

Vancouver Heritage Commission on Dec. 11, 2006 at city hall,

the "history/heritage value" of the Imperial building was considered.

But the commission merely recommended "the commemoration of

the historic Imperial Theatre in an appropriate form." One translation

of that recommendation could mean merely putting up a plaque.

Photo: Stuart Thomson, 1925. VPL#11032 |

But

the Imperial is one of the last examples of Vancouver's original

theatres on the East Side, and spaces like it are much needed

by arts groups in the city. A few blocks away, the Pantages

Theatre is being restored to the tune of $10 million. Why no

save-the-Imperial campaign?

"The

Imperial's fate was sealed by the time the developer walked

into city hall," says heritage advocate and historian John Atkins,

referring to the power of the Vancouver Heritage Register in

determining the preservation or destruction of an old building

in this city.

Adopted

in 1986, the Vancouver Heritage Register cannot legally protect

a structure but it does have various processes and incentives

that go a long way towards keeping a heritage building up. The

three buildings of the Hotel Pacific that Porte will restore

are all on the heritage register. The Imperial/Venus building

is not. "You are starting from a losing position," says Atkins.

The

City of Vancouver website states that in forming the register,

a study team looked "at every street in the city to identify

notable buildings." Atkins refers to this as a "drive by" and

suggests that "a pink porno theatre on the East Side obviously

didn't impress the surveyors."

Why

is the Imperial building worth preserving? "For one thing, it's

still standing," he says.

But

he's one of the few people willing to speak up on the building's

behalf. When the Venus comes down and the new tower comes up,

maybe someone will open an adult DVD store on the retail level

and call it The Venus in tribute.

It

wasn't supposed to end this way. The Imperial Theatre began

life proudly, built for the Canadian Theatre

and Amusement Company in 1912. George B. Purvis was architect

and proprietor was J. J. McDonald. According to an Anvil Press

publication The Door Is Open, by Bart Campbell, the

Imperial "alternated vaudeville acts and movies," and legendary

performers such as Jack Benny and the Marx Brothers played there.

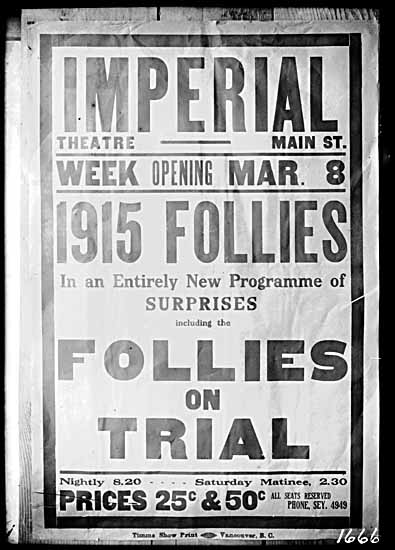

Photo: Philip Timms. VPL#7331

|

Unfortunately

the downward spiral began early. Shows moved on from the Imperial

quickly. The popular local wife-and-husband acting team of Isabelle

Fletcher and Charles Ayres started a stock company at the theatre

but failed to produce a hit. Archived newspaper articles blame

variously the competition from the more established Avenue Theatre

across the street (now demolished), the shift in locale of the

entertainment district north to Hastings, the rise of motion

pictures, or some mysterious jinx.

An

interesting Chinatown connection emerged in

the 1920s when Chinese businessmen

turned the Imperial into a Cantonese opera house. Wing

Chung Ng, UBC doctoral graduate and professor of history at

University of Texas at Austin, studies the history of Cantonese

Opera in Vancouver and provided key information from the local

Chinese-language newspaper The Chinese

Times: "According to a theatre ad on Sept 1, 1921, a group of

nine Chinese merchants acquired the use of the former Imperial

Theatre and turned it into an opera house for troupes from China.

The first such company arrived in Vancouver on Sept. 5 and started

performing on the evening of Sept 9. The troupe was called Lok

Man Lin, and its season lasted till February of 1922."

But

by 1927, the Imperial was no longer

an entertainment house of any kind. It had been re-christened

a "temple"-first the Pyramid then the Emanuel-as suited its

new purpose as a Pentecostal church.

Unfortunately, God also wasn't a smash at the venue and by 1932

it fell into the City of Vancouver's hands as a result of tax

arrears.

The

Imperial then narrowly avoided demolition. A 1943

Vancouver News-Herald article reported that city council considered

replacing the Imperial with three stores, "but when it was figured

that to tear down the old building and erect the stores would

cost around $10,000 the plan was declared uneconomic and dropped."

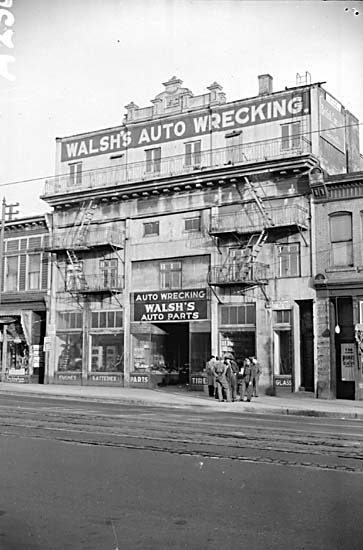

The

Imperial postponed its date with destiny, only to be resurrected

rather ignobly as Walsh's Auto Parts and

Wrecking. A 1941 local newspaper article by Ernest Walter floridly

relates that "where now stands a grimy-faced lad, beating a

mudguard into shape with a hammer, the heroine once stood and

shrieked, 'Unhand me, Colonel Cordite!'"

Photo: Jack Lindsay, Vancouver News-Herald 1943

CVA#1184-189

|

Dismantling

old cars onstage occurred daily for an unprecedented 27-year

run. When it ended in 1967 the

theatre was left a greasy relic. But amazingly the old Imperial

was reinvented once more.

The

City of Vancouver Archives hold a single sheet of typed information

on the Imperial, which lists use as a "Chinese moving picture

house." As for the date, the anonymous researcher only noted,

"at one time; when, don't know." But indeed a man named Henry

Chow had bought the building with plans to show old movies from

Hong Kong. A full renovation was done. Barry Godfrey, the late

Chow's son-in-law, recalls that Chow "did show the Chinese movies,

but it only lasted a month or two."

So

Chow changed plans and the Night &

Day theatre was born in

1970, given over to adults-only

16mm films. Cinemas dedicated to skin flicks were still spreading

across North America and this was the first one in Vancouver.

By comparison, the venerable "art house" Pacific Cinematheque

didn't open until 1972. In a curious mirroring of the building's

vaudeville-and-movie roots, the Night & Day also featured

exotic dancers performing on stage between reel changes.

The

films themselves were amateur at best, often starring San Francisco

hippies. One such film, entitled Dirt Bike Banger, is so drearily

awful, and has so little sex (which is simulated anyway) or

even nudity that one wonders how even the most titillation-desperate

patron could have tolerated it. The best part is the opening

shot of a motorcycle being parked.

Yet

the customers still came, and when the theatre was renamed

Venus in 1978, it had its own in-house logo, which proudly

showed at the beginning of the movies, along with a strip of

film that declared "good clean sex." By the mid-'90s management

installed video equipment, though Godfrey notes that as late

as 2000, when he sold the business, he was still showing films

occasionally, "because our regular customers liked some of them."

It

was the "tiny ad" campaign of the Venus that caught the eye

of a certain precocious future writer. Powerful as young Michael

Turner's triple-bill experience was, he didn't return for another

20 years. "This time it was to make sure I got the opening of

The Pornographer's Poem right" he tells me. "Just being there-closing

my eyes and taking it in-brought back more than expected."

Turner

describes in his novel how his fictional counterpart encountered

the Venus: "I step into the light. The silver light. Hundreds

of seats. The backs of 10 heads. Silhouetted_ I still can't

see. But I end up front-and-centre. A mystery to me. To this

day."

Porte

Realty spent $5.16 million acquiring six properties in the 700

block of Main Street. One property not for sale was the small

red brick building beside the Venus. Leo Chow has operated his

Brickhouse bar in the back for

15 years, proudly calling it a "non-trendy local tavern." As

the Venus's closest neighbour, Chow has seen it all. "It's the

end of an era whatever people think of it," he says, admitting

he does have "a problem with the drug activity and shady people"

that have been more frequent in recent years. As for his upcoming

spiffy new neighbours as potential patrons of the Brickhouse,

Chow is undecided. "The condos are sort of like a mixed blessing.

Places like the Venus are what make these areas edgy and create

a certain mystique. Hopefully this will not change the dynamic."

The

edgy little secret of the remaining adult movie theatres is

that while they show strictly "straight" porn, the clientele

is largely men seeking the sexual company of other men. But

the Venus is different. Not only is it rare enough as a survivor

but its particular locale has made it into a specialized zone

of social interaction.

The

Downtown Eastside has long been an open market for hard drugs

as well as women who are addicted to them. And since the Venus

is an accessible and extremely dark space nearby, it has become

a haven for both of these activities. While the male action

takes place on the main floor, the prostitutes work the balcony-their

efforts highlighted by flares off the occasional crack cocaine

pipe.

The

conditions for the working girls in the balcony was covered

in the 2004 Courier feature. The Venus's off-the-street environment

protects the prostitutes from the danger of violence from predators

in anonymous cars, but according to prostitution activist Jamie

Lee Hamilton, that security is offset by male patrons taking

excessive liberties with vulnerable hookers. "Too often the

house girls of the Venus were subjected to abuse and degradation,"

she says. "While I'm not unhappy to see the Venus finally close.

I am concerned over what the future may bring for these girls

who will now be forced out onto the street."

For

now, a unique and vital culture, however illicit, thrives inside

the Imperial building, drawing together elements mainstream

society wants hidden-pornography, gay cruising, prostitution

and drug use. Is the proprietor who turns a blind eye uncaring

or merely facilitating a needed function in society?

The

current Venus owners are a married couple from mainland China

with no particular interest in adult movies. When I first began

researching the Venus several years back, the husband, Dong

Xu, quickly asked if I wanted to buy the old stockpile of adult

films that previous owners had left behind. (I am now an expert

on the divergent sociological underpinnings between Million

Dollar Mona and Hundred Dollar Wife.)

Yet

if there is a potential hitch in the developer's plans, it is

not city hall but Dong Xu. With translation help from an employee

named Philip, Dong assures me he has "four and a half years

left on our lease" and everything is business as usual.

But

heritage advocate John Atkins has resigned himself to the Imperial's

fate, a reminder that "lack of historical context lets buildings

get overlooked." He hopes to at least document the inside of

the Imperial before it goes. "A proper survey of the interior

would probably uncover more of the original design than people

assume is there," he says.

While

the stigma of porn may have led heritage arbiters to overlook

the Imperial Theatre, it is true that most of the interior and

the exterior of the building were long ago stripped of their

original features. The Heritage Commission underscored this

in its statement of regret on the "loss of the remnants of the

historic Imperial Theatre Building."

"Built

heritage" is the focus of most formal heritage groups, and the

city's heritage register also bases evaluations on the physical

structure. But the quality of "heritage value" is also defined

as having "historical, cultural, aesthetic, scientific or educational

worth." According to some, the Venus has much of this second

kind of heritage, one not so much reliant on the architecture

as the unspoken layers of personal meaning for people who function

within it.

Turner

notes the full flowering of that culture on his last visit to

the Venus. On a tour through the building we find ourselves

in the original projection room with the two Eiki 520 Premier

projectors abandoned on a table and aiming their lenses toward

the screen below where Turner and friend sat over 25 years ago.

"What we saw in the Venus that night provided us a private language

that we continue to use to this day," Turner comments.

For

him, the Venus is about the "sexscapes" he saw during his final

visit. "The place is in a state of disrepair, no longer functioning

as a site for viewing stuff on a screen, but one where people

turned tricks in the balcony, while others sat around and watched.

I had never seen anything like it. It might sound revolting

to some, but that's what I'll miss when they tear this building

down. Not the building, but the behaviour. What went on inside

it."

|